Most of the opposition to President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita (IBK) has hailed the August 18, 2020 coup d’état. They were hoping that the National Council for People Salvation (CNSP) would spare Mali from violent terrorists’ attacks and inter community killings as well as preventing a disastrous economic, social and political crisis. The return to civilians rule after a short Transition was also part of their expectations. The rampant occupation of the political space by the military has disseminated doubts.

Most of the opposition to President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita (IBK) has hailed the August 18, 2020 coup d’état. They were hoping that the National Council for People Salvation (CNSP) would spare Mali from violent terrorists’ attacks and inter community killings as well as preventing a disastrous economic, social and political crisis. The return to civilians rule after a short Transition was also part of their expectations. The rampant occupation of the political space by the military has disseminated doubts.

The premises for militarization began with the installation of a former defense minister, retired Colonel Ba Ndaw, as Head of State, on September 25. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) had demanded a civilian. A daring makeup, which was accepted, encouraged the junta to pick, two days later, as Prime Minister, former Minister of Foreign Affairs (2004 – 2009), the experienced Moctar Ouane. In the government appointed on October 5, the military holds the strategic positions of Defense and Veterans Affairs; Territorial Administration and Decentralization; Security and Civilian Protection; National Reconciliation.

On November 25, 2020, the Council of Ministers has appointed 13 military governors of regions, out of a total of 20. All are said to be close to the vice-president of the government, Colonel Assimi Goita.

The only figure of the CNSP until then still ‘’free’’, Colonel Malick Diaw, number two of the junta, was brought on December 5 as the Chair of the National Transitional Council (CNT). The Transition legislative body is called upon to lead the reforms: restoration and strengthening of defense and security, promotion of good governance, overhaul of the education system, political and institutional reforms, adoption of a social stability pact and and finally, the organization of general elections.

To compose the CNT, the junta made its political purchases, everywhere on the national scene: soldiers, but also personalities of the former parliamentary majority and opposition, members of the Movement of June 5-Rassemblement des Forces Patriotiques (M5-RFP), personalities from former rebel armed groups, representatives of civil society and a music star, Salif Keïta. The recruitment criterion escapes the political parties and even some lucky elected officials. It also has 22 soldiers as members.

IBK’s frustrated adversaries.

Members of the M5-RFP, a politico-religious strike force, under the leadership of Imam Mahmoud Dicko, who fought former President IBK until his fall, stepped up to denounce the Transition Charter and the installation of a military regime. In the name of the role it played in « the struggle », the M5-RFP claimed not only the presidency of the CNT, but also a quarter of the seats in the legislative body. In fact, eight seats have been granted to it. Faced with this double failure, the Movement threatens to resume its “protest activities”. For its leaders, the CNSP is struck by a certain illegitimacy, for having marginalized them. The Movement is signaling to the military that it is doing well and is ready to fight again until its ultimate goal of changing the country governance system is achieved. In the eyes of the Movement, the junta personalities co-opted would rather form part of the “hostile forces”. Old and, perhaps, new walkers intend to be fully involved in managing the transition. The frustration of the Movement is all the greater since, to lull its vigilance, the junta has allegedly promised it the prime ministerial office and three quarters of the ministerial portfolios. Members of the M5-RFP risk practicing a form of political guerrilla warfare, throughout the Transition, to save its assets: support for measures aimed at improving governance and contesting those aimed at maintaining or strengthening of practices fought under IBK.

The M5-RFP has found an objective ally in the National Union of Mali Workers (UNTM), a union that called a strike from Monday 14 December to Friday 18 December. Its demands relate to the harmonization of salary scales and bonuses and allowances in the civil service, or to the fate of dismissed workers in privatized State enterprises. The President of the Transition, who suspects a « political scheme », had provoked the ire of its members by declaring: « In Mali current state, how someone who enjoys all his abilities can speak of strike?’’ A symptomatic nervousness of the relations between the Transition and Civil Society Organizations.

The slowness in operationalizing the organs of the Transition, i.e., three months and three weeks after the coup, rumors of the threats of the Prime Minister and the President resignations as well as the appearance of the vice-president grabbing power seem to indicate the degree of this interim power fragility. Confidence between the Transition main players remains to be built, that between the junta and the political parties, too. Witness this week arrest of seven prominent personalities including two senior executives from the Public Treasury, the director of the Malian Pari Mutuel Urbain (PMU), a private radio columnist and activist. These various arrests, made by state security, and yet to be explained to the public, are said to be linked to a « project to destabilize the Transition ».

In defense or remembering the military

Parties from the former presidential majority, as well as the political opposition under IBK, are making similar grievances against the junta. But personalities also plead for tolerance with regard to the Transition, due to the fact that it is an exceptional regime, which cannot survive without legal and political tinkering in the face of a political class accustomed to ‘’having their soup’’ under all regimes since 1992

The misunderstandings are likely to worsen as the Transition roadmap unfolds and especially as the elections dates get closer. Having secured strategic positions, the military is giving itself the means to influence future elections, in a decisive manner. They have the choice of weapons. The new strongman can resign to retire from the military, then run for office. A scenario more perfected and more mastered than that concocted by President Amadou Toumani Touré, between 1992 and 2001. The junta can also encourage a personality, favorable to its views on governance, to run and then, without firing a shot, make him Mali future president. Adversaries of the militarization have these fears in their sights.

Since the start of ATT’s second term in 2007, part of the military hierarchy has criticized its own superiors and the civilian authorities for not listening enough to soldiers’ complaints and to being insensitive to their living and fighting conditions. The governance of the two entities has often been criticized. Under IBK, these blames flourished, with colossal embezzlement at the Ministry of Defense, the chairmanship of the Defense Commission in the National Assembly then chaired by his son. Images circulating on social media, of generals feasting with billions and trips to Spain of the heir, while soldiers died on the front, accelerated IBK’s downfall. The return to business of this politico-military class could create further trouble for the officers of the Transition. By controlling these strategic governmental positions, they secure themselves. Meanwhile, the country’s security has hardly improved.

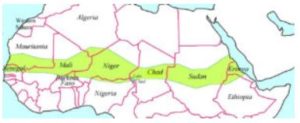

Since early October, the town of Farabougou, center of the country, has been subject to a jihadist blockade. However, good news has come from two neighboring countries. Burkina Faso was able to hold its presidential and legislative elections in relative peace except for one attack, 14 soldiers killed, bringing sorrow on an election campaign that lasted three weeks. Algeria has just amended its constitution by allowing the President to deploy troops abroad.

Finally, with the implementation of the Transition roadmap, there is hope – to be encouraged – that Mali will be able to organize its elections in a peaceful environment in eighteen months.

By André Marie Pouya, Journaliste, Consultant Centre4s.org